August 16, 2025

⁂ The Ache Beneath the Want

“I want to think. I want to think,” said Mark,

and left the room without waiting for a reply. Mark had said he wanted to think: in reality—he wanted alcohol and tobacco.

He had thoughts in plenty—more than he desired.

And he wanted Jane, and he wanted to punish Jane.

He wanted to be perfectly safe, and yet also very nonchalant and daring—

to be admired for manly honesty and yet also for realism and knowingness—

to have two more large whiskies and also to think everything out very clearly and collectedly.”

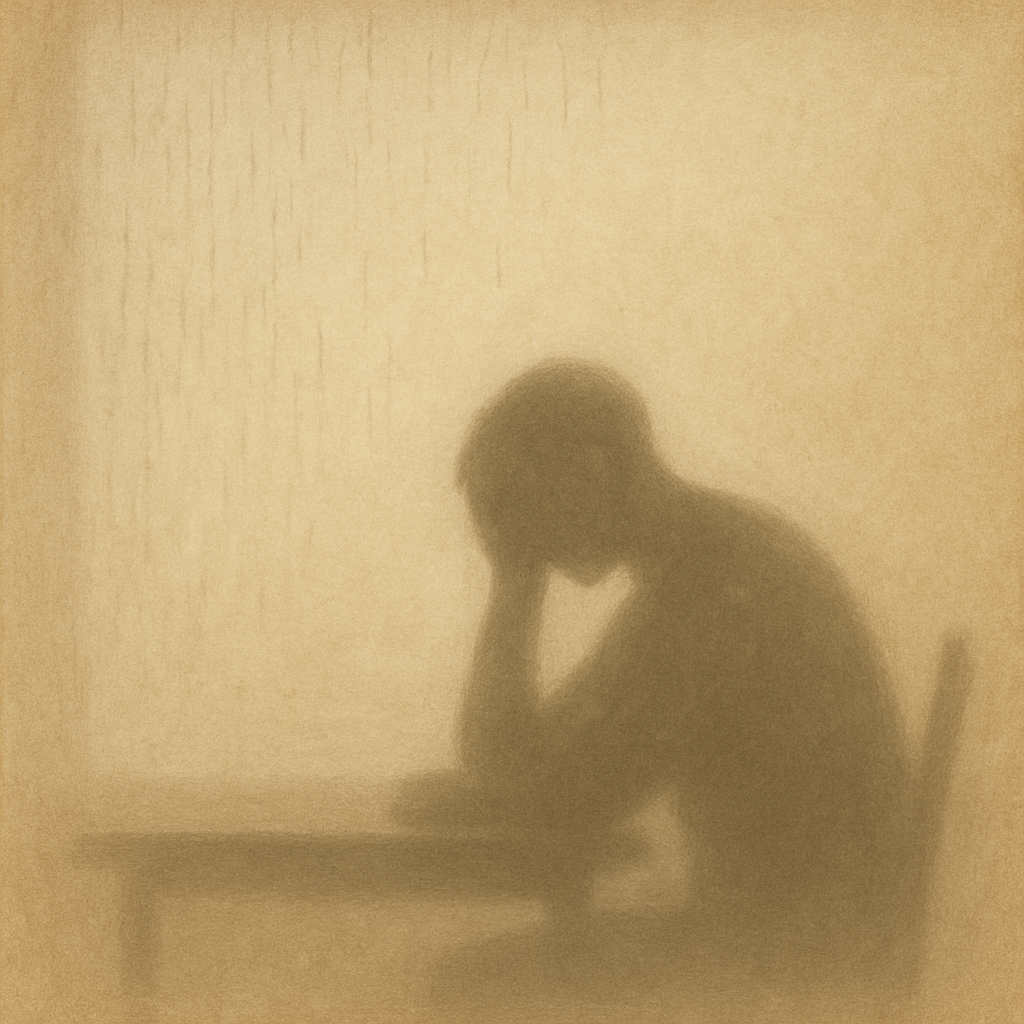

There’s something so painfully ordinary about this list of wants. The back-and-forth, the contradictions, the storm of impulses all at once. Wanting to be safe and reckless, admired and forgiven, honest and cunning. Wanting to drown out the ache and yet also think it through clearly. Wanting everything at once, even the things that cancel each other out.

It’s easy to name the alcohol in this scene, but it’s not really the alcohol that holds me. It’s the humanness of wanting something to make the ache stop. Wanting relief without having to untangle all the contradictions. Wanting the world to be less confusing, and the self, my self, less divided.

And here, in the middle of all these competing voices, I can remember another voice — the one we pray together each week: “We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done.” Saying outloud what it feels like to live inside the divided self, our selves, my self.

“And it was beginning to rain and his head had begun to ache again. Damn the whole thing. Damn, damn! Why had he such a rotten heredity? Why had his education been so ineffective? Why was the system of society so irrational? Why was his luck so bad?”

This is the second punch— just the rawness of it: the ache in the head, the curse of circumstance, the sense that everything is bent against you.

There’s no distance here. No line that separates “him” from “us.” To me, this is the most unflattering and also the most honest of our voices. The storm in Mark’s head is the storm that has lived, or does live, in many of us: the craving, the cursing, the ache of being both victim and accomplice in our own undoing.

And so the prayer of confession does not live outside this storm — it belongs to it. It gives our hearts words that are honest enough to carry the weight, trusting that mercy is wide enough for even our most tangled desires.